Lil Durk: The Voice

Photographs: Braylen Dion

Words: Atoosa Moinzadeh

PUBLISHED SPRING 2021/BRICK MAGAZINE

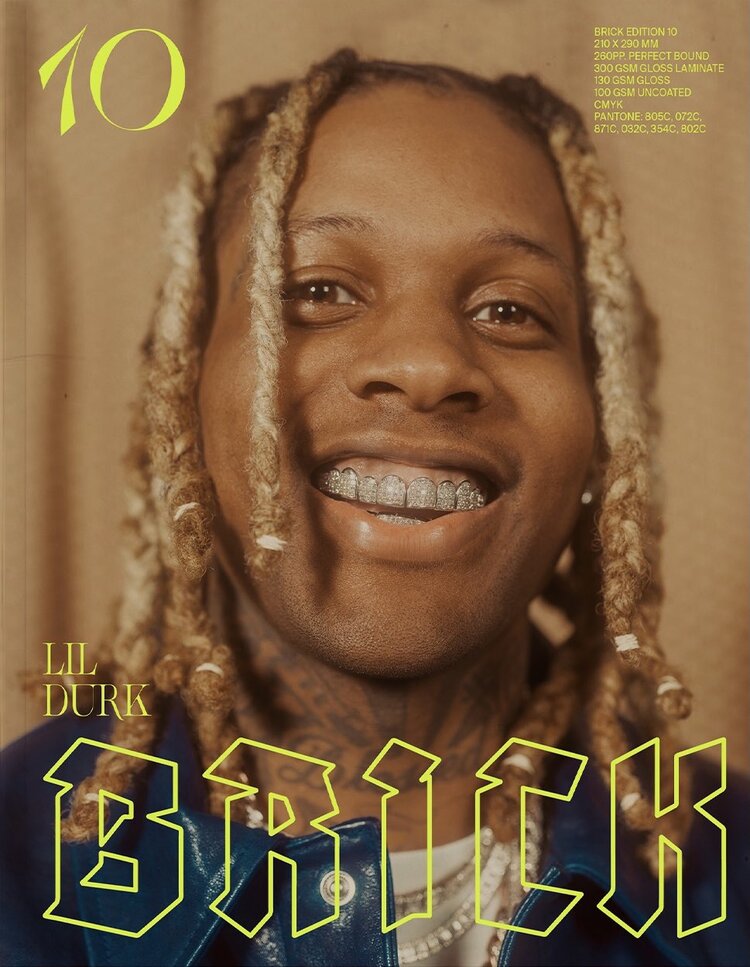

“I SWEAR, I’M not usually this scattered.” I’m sitting across from Lil Durk in the back of Chrisean Rose Studios in Midtown Atlanta, and he’s immersed in a very important text thread with his girlfriend India Royale. “We’re texting about furniture for our new house and all this other stuff, Durk tells me, his eyes lighting up. His face is framed by blonde braided locs, and a tattoo that reads “Angelo,” the name of his first son. When he looks down at India’s messages and smiles, his diamond-studded grill reflects back the screen’s glow. “We've been bouncing ideas off each other, and if I don't text back, I’ll lose my train of thought. My bad,” Durk laughs.

Durk showed up to his interview 30 minutes late, effortlessly rocking six chains and two watches, a Celine tee, an open Off-White button down, skinny jeans, and Dior runners. He just got done shooting a music video with emerging artist Coi Leray. “Lots of booze, waking people up, stuff like that,” he says of the “No More Parties” concept. While the 28-year-old Chicago rapper gave several radio interviews in 2020, this will be his first print magazine cover story, and first photoshoot in some time. “I be real picky with who I do press with, I try to choose magazines that I’m interested in—and when Covid hit, it just made everything worse,” Durk starts. A member of his entourage pops around the corner to check on him a couple of times, but we get privacy for the most part. “It took a whole year,” he continues. “But I’m happy. Now we're here.”

One decade in, Durk just had the most commercially successful year of his career. Just Cuz Y’all Waited 2 debuted at #2 in May 2020 and went gold. A feature on Drake’s “Laugh Now, Cry Later” cemented his mainstream palatability, and earned his first Grammy nominations: “I feel like everybody can have a Drake song if I’ve got one,” he told Interview magazine in December. He went from benefiting from “the Drake effect” to showing how much weight “the Durk effect” holds, landing newcomer Pooh Shiesty on the Billboard Hot 100 chart with a feature on “Back in Blood.” As one of the pioneers of the Chicago Drill scene—a city he’s characterized as having “too many followers, not enough leaders”—Durk’s impact on a generation is undeniable with the recent rise of artists like King Von, Calboy, and Polo G. Durk tells me that with the exception of tours halting, the pandemic hasn’t hampered his productivity: his “survival skills kicked in,” and he adapted to the solitude quickly. “It really didn't ever affect me because I was already a studio junkie - I had the studio set up in the house,” he says. “I had in-house producers sending me beats. I have a hard drive full of beats I'll never use. So in the midst of everything going crazy, I still had the sauce.” Durk adds that the conditions of shelter-in-place helped rally his fanbase, too. “Everybody’s attention on. Everyone’s in the house, taking in music, movies, and books,” he says. Durk’s knack for storytelling favors active listening, and he’s the kind of artist you truly get to know if you’re paying close attention. “When I dropped Just Cause Y'all Waited 2, it got this crazy reaction,” he continues. “I had Nicki Minaj and Drake hitting me up. I was like, ‘Oh yes, we’re getting some progress.’” To Durk, who’s six albums and twelve mixtapes in, the recognition feels good. “Just to know you can hit the culture that hard,” he says. “And it's different for me, some people counted me out for ten years … you would think … to still have that effect,” Durk pauses—it’s as if he’s still in the midst of processing just how far he’s come. “I neve had that effect, matter of fact. So to see it hands-on was crazy.”

But Durk’s latest album, The Voice, isn’t celebratory in tone. Much of it is a poignant look into the pain, loss, and tragedy that have surrounded his ascent. “I always found my lane was to be soulful, to speak to my past,” Durk tells me. I’m immediately reminded of the song “Refugee,” a collage of various flashpoints in his life. “I’m a ‘what I come from, what I've been through’ type. It made me expose a deeper side of myself.” The Voice’s cover, and much of its content, are in tribute to his childhood friend and Only The Family (OTF) label artist King Von, who was tragically murdered in November, just south of here. I recognize that this is Durk’s first interview since Von’s death—in fact, as I learned 15 minutes before Durk’s arrival, it’s a subject to avoid. “He’s been pretty shut down these past few months,” his longtime manager Ola told me. Durk’s vulnerability on The Voice is as deep as we’re going to hear on the subject—at least for a while. "I knew I needed to talk about this on the mic and see how the fans react to it, see how the streets react to it,” he reflects. “And I recorded a lot of songs that I'll never put out. They were just for me to get me out my feelings.”

Durk’s career has outlasted legal troubles, a hindering deal with a major label, betrayal, addiction, and numerous deaths. For the rapper to have entered what music critic Yoh Phillips recently called his “second act,” in spite of it all, takes a certain level of tenacity—and on charting songs like “Finesse Out The Gang Way,” Durk acknowledges that too. Having just appeared on the soundtrack for Judas and the Black Messiah, Durk tells me the rest of the year promises a full catalogue: an OTF compilation album, two joint projects, with Metro Boomin and Lil Baby respectively, and hopefully concerts. “Baby and I are just recording, just having fun,” he says of their project, which he confirmed just yesterday. “During the recordings, we'll get the names. You'll see what type of vibe it's going to be. We know it's always gonna be the street, club music, talkin’ about females. It's the same thing, but I put my all behind mine.”

When I ask Durk what kept him motivated all these years— beyond India, and his six children remaining top priorities—his answer is unfiltered: “It's a little different for me because I get motivated off of doubt. Hate. I get motivated off negativity from close people who supposedly want you to win. They just be behind your back talking, ‘Oh he ain't never finna…’ I had a friend before tell me, ‘You not gonna start rapping. You should start signing artists.’ I had somebody tell me, ‘You should just make a straight R&B album.’ I went through all the type of phases where it was like, ‘I'm finna prove them wrong. I'm finna prove them wrong.’’ Over the course of an hour, I learn that the most important thing to understand about Durk’s story—and music—isn’t that he overcame the odds. It’s that Durk has remained unflinchingly authentic. “I've just stood 10 toes,” he asserts. “I just stayed me.”

‡‡‡

FIVE YEARS AGO, Lil Durk gave Complex a tour of Englewood on Chicago’s South Side. The first stop was his grandmother’s three bedroom home situated on 72nd and Halsted, where he spent his formative years. Born Durk Derrick Banks, the rapper experienced instability early on: his father, Dontay “Big Durk” Banks, was incarcerated when he was just seven months old, while his mother worked back to back shifts as a nurse. Durk remembers staying out as late as 4 or 5 a.m. before he was a teenager, sometimes going without food. “I came from one house, ten people, there were even days when the lights were off,” he said, as viewers got a look into the then-gutted townhome. As he grew older, Durk found that violence in his city only increased, especially in his high school years. “I used to be posted up right here, this is where we’d have get-togethers for all the guys who’d died,” he commented as he drove past the Hamilton Park Cultural Center. “Then it started to get too crazy, kids were dying … kids were getting killed on purpose.”

In many interviews, Durk has said that his first run-in with the law in 2011, and fatherhood, are what pushed him to take music seriously. “I was 17 and out of school, living with my mom, starving, not eating, getting locked up, no focus, no guidance,” Durk said in 2015. “When you ain't got no guidance, you can't do too much. But then I had my first son and started working. I got the right people around me.” Like many of his Chicago Drill peers (Chief Keef, Lil Reese, Fredo Santana), his music, which focused on his life experiences, began to generate buzz on Myspace and YouTube. Following the formation of the OTF collective, Durk released his debut mixtape, I’m a Hitta in 2011.

Andrew Barber, music critic and founder of blog Fake Shore Drive, remembers discovering Lil Durk when he heard “I Get Paid” featuring King Louie, which he describes as “a Chicago footwork inspired juke song.” That production, combined with Durk’s melodic style, was something that sounded completely new to the Chicago scene at the time. “The genre wasn’t even called Drill yet, and the song really stood out to me,” he told me over the phone. “Durk had taken elements of other things that were popular at the time and ran with it, which made him different from guys like Chief Keef. That’s what the Midwest does well in general. It takes elements of different regions and makes it their own thing.” Barber said that when a 30-second snippet of the era-defining “L’s Anthem,” began circulating in 2012, he knew the rapper was about to blow. “Drill got an initial backlash from an older generation at the time, but the younger crowds loved it,” he says. Barber was right—by that point, he’d caught French Montana’s attention, and Def Jam Records was getting ready to ink up an offer.

“The Drill scene exploded, and it felt like Chicago had become the largest regional market in rap, for the first time in a while,” Barber remembers. Everyone wanted in: and it didn’t take long for the narratives of artists like Durk—and the neighborhoods they grew up in—to fall victim to voyeurism. “People were suddenly interested in something they didn’t originally understand, or care about,” says Barber, in reference to the gang violence impacting Chicago. Notably, Noisey featured Durk in a documentary series called Chiraq. “We’re in the windy city, Chicago, home of deep dish pizza, The Bears, and the highest murder rate in America,” opens the first episode, “Welcome to Chiraq.” “Chicago’s also home to Drill music, brand new rap made by teenagers about killing people.” Concerts were being targeted by the Chicago Police Department well before the documentary was released, which Durk shed light on in an episode titled “Lil Durk Terrifies the City.” “Every time someone gets killed or something, they say it’s because of our music,” he told Noisey. “I know it’s way deeper than that. They don’t want us doing nothing good for ourselves.”

“I ALWAYS FOUND MY LANE WAS TO BE SOULFUL,

TO SPEAK TO MY PAST.”

Durk and Reese were among the first Chicago rappers to sign a deal with Def Jam without an imprint—but much like the media spin, the music industry that desperately wanted to buy in was experiencing a disconnect. At the time of Durk’s deal, streaming metrics weren’t being factored in, and regime changes further complicated things, as Barber pointed out. There’s one thing Durk repeatedly insists on as we talk about this period: “My sound was being overlooked.” His music continued to verge towards traditional melodies while keeping things street—something that wouldn’t be fully appreciated until the Drill genre matured. Even as it did, many of its stars faded in and out of visibility, but Durk never left the mainstream. Over the duration of his deal, Durk earned a spot in the 2014 XXL Freshman list, released two albums and several mixtapes, and watched two singles go gold. Even as the rapper remained heavily involved in OTF, the five year period with Def Jam still felt stifling, he says. “I became too dependent,” Durk reflects now. “There was just no energy, no effort. And I came off thinking like, ‘Oh, [the label was] supposed to do this.’ And they showed me like the total opposite.’ So I had to learn it, to see what I had to go through.”

At some point in 2017, before leaving Def Jam, Durk moved to Atlanta. The CPD’s harassment and surveillance were limiting opportunities for him in Chicago. By then, Drill’s biggest star, Chief Keef, had already been exiled from the city. “I had to get away from what was going on in Chicago … there’s the violence that's number one, and you can't do shows in the city,” he tells me. “There’s always BS going on. You’re like a crab in a bucket. They don't want to see you win. The artists weren't really working with each other. So I said to myself, ‘I'm going to Atlanta, just leaving everything behind, with nothing.’” Durk tells me that Atlanta was where he really woke up to how he could thrive outside of the label’s infrastructure, with a strong network. Upon arrival, Durk set up an in-house studio, and linked up with Jerry Production, a music video producer he still works with to this day. “We had shot the video for ‘Make It Out,’ and that's all just really the start of everything,” Durk says. In the years leading up to his relocation, he’d already built relationships with the likes of Future, Young Thug, and Lil Baby, which set him up for success. “This is the number one music city. You have rappers, producers, singers, songwriters, politics. What else? It's just, everything is here. And people from Atlanta work with each other. They help each other. You don’t have that in Chicago.” His first releases after parting ways with Def Jam, Just Cause Y’all Waited, followed by Signed to the Streets 3, boasted all-star rosters of producers and features. By 2018, it felt like Durk had finally unlocked something. “He kept fighting, he kept working, he kept releasing music... he basically stayed in the gym and worked on his jumper,” says Barber. “It’s unbelievable for someone to be almost ten years into their career, and to have their biggest moment.”

I ask Durk what’s changed in the past decade. “In Chicago, I see history repeating itself, just with different faces,” he responds, stressing that it’s important for young artists to branch out. “But our whole goal is to not be the next story like, ‘He had the whole world in his hands, then fell off. Where he at? This much money, now he broke. He be on the next block, cleaning up the street. I'd hear those stories so much and be like, ‘That can't be me. I got to change.’” Today, the landscape for Drill music looks vastly different—it’s alive and well in Chicago, has sparked a renaissance in New York City, and has gone international to the UK. “It feels good because your name will always pop up in there, our names circulate every time you hear the word Drill,” Durk tells me. The music that Durk makes now sounds vastly different, but his street sensibilities remain close. And above all, innovation excites him. “Drill’s becoming fun again. And it ain't the end. You can keep going and make a whole ‘nother genre or a whole ‘nother power move. It’s about how the world continues to do it.”

‡‡‡

DURK IS IN a green velour tracksuit and white Air Force 1s—the third out of four looks for his photoshoot—and is fussing in the mirror. I’ve been learning a lot about his preferences today: for one, he absolutely refuses to wear baggy pants. He also denies hair and makeup, and is indifferent to sunglasses. But at no point is Durk difficult to work with: he’s just incredibly sure of himself, and doesn’t hesitate to politely assert that. In the event that the stylist pulls anything he’s not a fan of, his face deadpans until his discomfort is made clear, and then he breaks the tension with a smile. By the time Durk and photographer Braylen Dion have started this portion of the shoot, Durk’s entourage and the production crew have become comfortable with one another. His manager Ola has ordered us a dozen Impossible Burgers (I learn that in addition to being a devout Muslim, Durk is a vegetarian), and bonds have been forged. Durk is in a relaxed, playful mood, and has eased into asking us for input on what he’s wearing.

As I get this partial look into Durk’s strong ecosystem, I’m reminded of a point in our conversation where Durk and I discussed the concept of leadership. “When I say, ‘I want to be the voice. I want to make you feel this,’ it’s about relating to people and teaching them stuff,” Durk explained. Durk’s humility stood out through the duration of our interview—even ten years in, Durk tells me that he’s still learning from veterans like Future, as well as from newcomers like his OTF signees. “Give and get knowledge. That’s what it’s about. The people I've learnt it from, and got knowledge from, I take that to my people, they take it to their people, just like a chain reaction.” He describes the OTF label and collective as “a family, and a team” that’s here to support its members in anything they set their minds to: music, acting, even sports. “We know it don't last forever. We have a lot of artists, and this is like the stepping ground, where it's like, ‘You earn here. You take it elsewhere.’ Get your money from here. Put it in here. I'm trying to set things up like Roc-a-Fella.”

As the shoot begins to wind down, Durk’s final look is missing something. Ola walks over to the set with a navy blue jewelry box. On the outside, a silver plate has “The Voice'' inscribed on it; inside is the infamous “Icebox” logo. Durk rummages through a bounty of options, including a chain dedicated to his late cousin Nuski, a cuban link choker with an “Allah” charm, and diamond studded rings. Then Durk calls out for his cousin, OTF signee C3, who I’d coincidentally been chatting with for the past 15 minutes or so. C3 has been building his music career for the past few years, and currently splits his time between Atlanta and Chicago—Durk has obviously been a big influence. “You could say he mentors me musically, he’s good at what he does,” C3 says. I realize he’s wearing his big cousin’s signature OTF diamond chain. He poses one final question to me before he hands it to Durk. “Who can’t learn from him?” ︎